I have seen it work. As a graduate student, I researched cover crops in a California dryland wheat system, comparing a wheat-fallow system to one with a cover crop replacing fallow (McGuire et al., 1998). A wet winter allowed for successful wheat yields in both systems. However, research results suggest that this is often the exception in dryland agriculture. More often, water use by the cover crop reduces the yield of the following cash crop.

This is a problem for improving soil health in these systems. Restoring soil organic matter levels is difficult with long periods of fallow without the addition of plant material to the soil for processing by microbes. Regenerative agriculture has proposed several solutions to this cover crop problem. First, cover crops may allow for greater infiltration rates, thereby saving enough water from running off to make up for the water used to grow the cover crop. Some claim that multi-species cover crops use water more efficiently than monocultures. Finally, it is claimed that planting cover crops could promote more rainfall, thus compensating for the water use by the cover crop.

Let’s explore the evidence for these claims, and an alternative that may be more effective than cover crops in some dryland cropping systems.

It’s all about the water

Unlike crops in rainfed regions, dryland crops cannot be produced using growing season precipitation alone; they must also use stored soil water (Robinson and Nielsen, 2015). This is where cover crops become a problem rather than a solution.

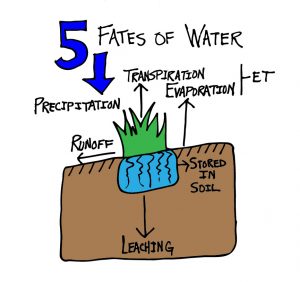

Water from precipitation is destined for one of five pathways:

- Water can runoff. Improved infiltration can reduce runoff.

- Water can leach below the root zone. Crops or cover crops can intercept this water, but if too much water falls too quickly, they cannot prevent leaching.

- Water can evaporate. Covering the soil with living or dead plants can reduce evaporation by blocking wind and sunlight.

- Water can be transpired through plants. In any region, biomass produced will be proportional to water used. Management should aim to divert more water through transpiration.

- Or water can be stored in the soil. This water is subject to either transpiration or evaporation.

Cover crop biomass -roots, root exudates, and shoots – is needed to obtain many of the benefits of cover crops; weed suppression, soil organic matter, nutrient scavenging, and soil biology activity. Even erosion control requires a minimum amount of biomass to protect the soil. However, biomass production uses water. So, in dryland systems, cover crops are a tradeoff of water use for biomass. If a cover crop uses more water than is gained through increased infiltration, reduced runoff, or increased soil storage, the following crop yield will be reduced. The timing of cover crop water use relative to precipitation timing and amounts can determine the outcome. Let’s look at what researchers have found.

Meta-analyses find cover crops deplete water before cash crops

A few recent meta-analyses look at cover crops in dryland cropping. Adil et al. (2022) found, compared to fallow management, cover crops:

- Reduced soil water at wheat planting (240 observations).

- Reduced winter wheat yield (138 observations).

- And reduced water use efficiency (199 observations).

Another analysis of 38 studies (Garba et al., 2022) found yields decreased by an average of 11% after cover crops in temperate dryland environments. Overall, they estimated that an annual precipitation of 27” is needed to avoid reduced crop yields following cover crops. Although crop yield may not be the only relevant factor, this aspect of cover cropping adds risk to a cropping system that is already risky because of highly variable annual precipitation.

Cover crops in the Palouse?

A threshold of 27” eliminates nearly all the dryland cropping region from Eastern Washington (Figure 2), but averages like this do not consider many regional climate differences. Unfortunately, local research suggests the threshold may apply here.

- Doing on-farm research (12-17” of annual precipitation), Roberts (2018) found that cover crop’s use of water put fall crop germination at risk. The farmers in this study decided to pursue companion crops instead.

- On-farm research in Douglas County (9-12” annual precip.) found that cover crops reduced soil water levels compared to fallow. (Michel, 2022)

- More on-farm research at five sites in SE Washington (12-25” annual precip.) tested spring cover crops in place of fallow (Thompson, 2014). Fallow ground, even without residue cover, evaporated less than half of what the cover crop used. This resulted in much higher soil water levels after fallow than after the cover crops.

- Research from the University of Idaho (Kahl et al., 2022) found that a cover crop grown for forage reduced soil water by 2-4 inches compared to fallow. A model estimated that this would reduce following wheat yields in 50% of years.

In a similar Mediterranean climate in Southern Australia, Rose et al. (2022) reviewed the research and concluded that the benefits of cover crops do not balance the risks of water use and effects on dryland cash crops.

Even where cover crops can be grown in dryland systems without affecting cash crop yields, the benefits will only become discernible in the long-term because biomass production will be limited to save water. There is also the possibility of reversals of soil benefits resulting from drought years (Simon et al., 2022). It seems the conclusions of the meta-analyses are applicable here.

Details matter

As mentioned before, the timing and amount of precipitation can shift the results in favor of cover crops. When cover crops are growing during the rainy season (Figure 3) as practiced in California, they may be grown without adversely affecting soil water if they are terminated on time (DeVincentis et al., 2022). In the Garba et al. meta-analyses (2022), using cover crops in climates with significant rainfall during the cropping season had positive effects on crop yield. The opposite was true of climates with mostly winter precipitation.

Improved infiltration?

One suggested solution is that improved infiltration from cover cropping will make up for the water that they use. This can be the outcome, but only in specific conditions where significant rain falls on the growing cover crop or its residues. In all the negative results provided above, we can assume that improved infiltration did not replenish water used by cover crops. A two-year study in Kansas found cover crops increased the efficiency of precipitation storage over fallow, but this did not make up for the water used by the cover crops (Kuykendall, 2015).

One problem is the low biomass production of cover crops due to low precipitation or through early termination to reduce water use (Ghimire et al., 2023). In an 8-year Montana study, cover crops produced less than 1.5 dry tons per acre of biomass (Dagati and Miller, 2020). Because of this, it may take several years before any soil improvements can be measured, including for infiltration.

Do cover crop mixtures help?

Another claim by some in regenerative agriculture is that cover crop mixtures use water differently than monocultures (see examples in Nielsen et al., 2015). Several tests of this hypothesis have been done in dryland conditions (Kuykendall, 2015; Nielsen et al. 2015). With up to 10 species in tested mixtures, the diversity of the cover crop in both studies made no difference in water use. This conclusion is supported by our 2020 systematic review of cover crop mixtures vs. monocultures (Florence and McGuire, 2020) In the 18 comparisons of water use we found, there were no differences between the water use of the best cover crop mixtures and that of the best monocultures.

Plants make rain?

Finally, some claim that vegetation itself can produce more precipitation (here, here, and here). As often is the case, there is a grain of truth here. Transpiration by plants moves water into the atmosphere. And that water returns to the soil as precipitation. However, the process remains local only if the air mass stays in the area. This occurs only in humid regions like the Amazon and Congo (Staal et al., 2018). Stretching this tropical rainforest effect to the Great Plains or other arid regions is not supported; irrigation has not increased rainfall in arid West, nor have large reservoirs of evaporating water changed the surrounding rainfall.

Another effect of plants is called fog combing. As a Peace Corps volunteer in Ecuador, I saw this many times with eucalyptus trees making the soil beneath them wet while the surrounding soil was bone dry. Sometimes the trees were dripping as if it were raining. Fog combing occurs when humid air moves through vegetation, allowing continuous condensation which builds up and drips to the ground. It happens in rainforests, and in the California redwoods. It requires a unique combination of humidity, air temperature, and wind speed with some plant-specific factors. A study in Northern Germany (far from dryland conditions) looked to see if cover crops could comb fog. Although conditions were thought to be conducive to fog combing, they found no evidence of it in two years of monitoring cover crops (Selzer and Schubert, 2022).

“Cover crops are not universally beneficial” Garba et al. 2022

A workable alternative to cover crops

Cover crop use of water in dryland agriculture presents a series of tradeoffs:

- Water use for biomass production and associated soil health

- Water use and cash crop yield

- And so, soil health vs. cash crop yield

Most of the time, the benefits of cover cropping do not overcome their downsides and so are not commonly used in dryland cropping. However, there is a feasible alternative: in their meta-analysis, Adil et al. (2022) concludes that the best practice for soil water conservation and dryland crop production is no-till with retained crop residues. Managed well, crop residues can protect the soil from erosion, maintain some level of soil health, and conserve stored soil water.

Update

“Cover crops grown during summer fallow reduced soil nitrate-N, soil water, and wheat yields compared with chemical fallow, especially in the major wheat growing region of north central Montana.” 2012–2019 at four Montana location, https://acsess.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/agj2.21336, Open access.

References

Adil, M., S. Zhang, J. Wang, A.N. Shah, M. Tanveer, et al. 2022. Effects of Fallow Management Practices on Soil Water, Crop Yield and Water Use Efficiency in Winter Wheat Monoculture System: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Plant Science 13. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.825309 (accessed 17 February 2023).

Dagati, K., and P. Miller. 2020. Advancing Cover Crop Knowledge: Assessing the Role of Plant Diversity on Soil Change. USDA SARE.

DeVincentis, A., S. Solis, S. Rice, D. Zaccaria, R. Snyder, et al. 2022. Impacts of winter cover cropping on soil moisture and evapotranspiration in California’s specialty crop fields may be minimal during winter months. California Agriculture 76(1): 37–45.

Florence, A.M., and A.M. McGuire. 2020. Do diverse cover crop mixtures perform better than monocultures? A systematic review. Agronomy Journal 112(5). doi: 10.1002/agj2.20340.

Garba, I.I., L.W. Bell, and A. Williams. 2022. Cover crop legacy impacts on soil water and nitrogen dynamics, and on subsequent crop yields in drylands: a meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 42(3): 34. doi: 10.1007/s13593-022-00760-0.

Ghimire, R., W. Paye, M. Marsalis, and R. Sallenave. 2023. Using Cover Crops in New Mexico: Effects on Soil Moisture and Subsequent Cash Crops. CR-707, New Mexico State University.

Kahl, K., K. Boone, and Brooks. 2022. Forage Cover Crops in Dryland Wheat Rotations: Impacts on Soil Water, Nitrogen and Yield | Wheat & Small Grains | Washington State University. Wheat & Small Grains. https://smallgrains.wsu.edu/forage-cover-crops-in-dryland-wheat-rotations-impacts-on-soil-water-nitrogen-and-yield/ (accessed 17 February 2023).

Kuykendall, M.B. 2015. Biomass production and changes in soil water with cover crop species and mixtures following no-till winter wheat. https://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/19080 (accessed 29 May 2019).

McGuire, A.M., D.C. Bryant, and R.F. Denison. 1998. Wheat Yields, Nitrogen Uptake, and Soil Moisture Following Winter Legume Cover Crop vs. Fallow. Agronomy Journal 90(3): 404. doi: 10.2134/agronj1998.00021962009000030015x.

Michel, L. 2022. Large scale on-farm cover crop trials in dryland wheat fallow region of north-central Washington. WSU Thesis.

Nielsen, D.C., D.J. Lyon, G.W. Hergert, R.K. Higgins, F.J. Calderón, et al. 2015. Cover crop mixtures do not use water differently than single-species plantings. Agronomy Journal 107(3): 1025–1038.

Roberts, D. 2018. Cover crop and companion cropping for the inland northwest: an initial feasibility study. WSU Extension publication TB59E

Robinson, C., and D. Nielsen. 2015. The water conundrum of planting cover crops in the Great Plains: When is an inch not an inch? Crops & Soils 48(1): 24–31. doi: 10.2134/cs2015-48-1-7.

Rose, T.J., S. Parvin, E. Han, J. Condon, B.M. Flohr, et al. 2022. Prospects for summer cover crops in southern Australian semi-arid cropping systems. Agricultural Systems 200: 103415. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2022.103415.

Selzer, T., and S. Schubert. 2022. Water dynamics of cover crops: No evidence for relevant water input through occult precipitation. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science n/a(n/a). doi: 10.1111/jac.12631.

Simon, L.M., A.K. Obour, J.D. Holman, and K.L. Roozeboom. 2022. Long-term cover crop management effects on soil properties in dryland cropping systems. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 328: 107852. doi: 10.1016/j.agee.2022.107852.

Staal, A., O.A. Tuinenburg, J.H.C. Bosmans, M. Holmgren, E.H. van Nes, et al. 2018. Forest-rainfall cascades buffer against drought across the Amazon. Nature Clim Change 8(6): 539–543. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0177-y.

Thompson, W. 2014. Can Cover crops replace summer fallow. Cover crop resources, PaNDAS (pnwcovercrops.org), https://css.wsu.edu/oilseeds/files/2015/02/Thompson_3H_DS.pdf

Comments

Good morning,

You are right, Adil et al. (2022) concludes that no-till is “the best practice for soil water conservation in dryland crop production with retained crop residues.”,but what about the increase in soil compaction?

Real soil compaction must be avoided, but firmer soils, with increased bulk density, which often result from reducing tillage does not necessarily mean the soil will infiltrate water slower. After several years, the pores in no-till soils often result in higher infiltration rates despite higher bulk density, and the residue cover helps too.

I’ll respond to this like Dwayne Beck did to me when I complained that I could not get his Principles of No-till to work here in the Palouse, –“I earned my PHD developing the Principles, now you have to earn your PHD learning to apply them in your environment”. The same goes for Cover Crops. There are Principles for successfully regenerating soil health. Cover Crops are a necessary part of that process, –we need to learn how to use them in our environment. This article points out the problems, now, how do we mitigate them and proceed to the goal of regenerating soil health. Near-zero soil disturbance, and diverse mix in cover crops are necessary to support the biology essential for regenerating the health of our soils that we are systematically depleting through our farming practices that include cultivation and high inputs of fertilizer and chemicals. Weed resistance, soil compaction, soil stratification, pH, are issues that are receiving, once again, a voice from research, for “cultivation”, –the very thing that got us here in the first place. Cover crops are likely, most years, to reduce winter wheat yields in our Inland Northwest, semi-arid growing conditions. That’s a bitter pill as long as we have the option of acquiring adequate supplies of fertilizer and chemistry at a price we can afford. An option, is to take a little less, learn how to build up our soil to support crops with less costly inputs. Farm for the future by developing farming practices that support soil biology.

Another alternative, proposed by this research paper from Australia, is to use cover croppping “as a flexible choice grown under favourable precipitation and economic scenarios rather than for continuous fallow replacement.”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378429023002125

Thanks, Andrew, for another excellent contribution. The research you analyze rings true to my observations. I think it is important to note that there may be a bias toward positive results and positive but unproven hypotheses on what should work to improve soils. I have often been invited to visit cover crop trials which are the first year or two of experience by the farmers and advisors conducting the demonstrations. I rarely if ever hear about longer term trials or permanent adoption by farmers, except for some on the national speaking circuit, many of those have developed niche market income not directly related to their original base crops. I think most trials end up showing less than positive results and are quietly dropped.

I support the efforts of Tracy Eriksen and others in testing new ideas and being willing to invest in the present to improve soils for the future. I personally think that preventing soil erosion might be the best, and maybe the only practical and immediate remedy for preserving our soils. I hope we can find ways to supplement erosion-proof and runoff-resistant soils with more soil organic matter, but I am convinced that simply eliminating tillage will not do it. I don’t think a few months growth of annual cover crops will be worth the expense, and soil and surface residues are disturbed in planting the cover crop. In addition, in the years when the cover crop fails, you might be worse off for organic matter than some form of fallow. Rotations including a few years of perennial grass might be most helpful for durable organic matter (Wuest and Reardon, 2016, Surface and Root Inputs Produce Different Carbon/Phosphorus Ratios in Soil).

[…] cover crops cannot be grown consistently enough to work on hillsides, hilltops and clay nobs. Check out Andy Mcquire’s blog post from earlier this year outlining the challenges with water limitations and subsequent yield hits. […]